Jacques de Lalaing and the Belgian Senate’s 'historical fresco'

From 'Belgique fondant la monarchie' (Belgium establishing the monarchy)...

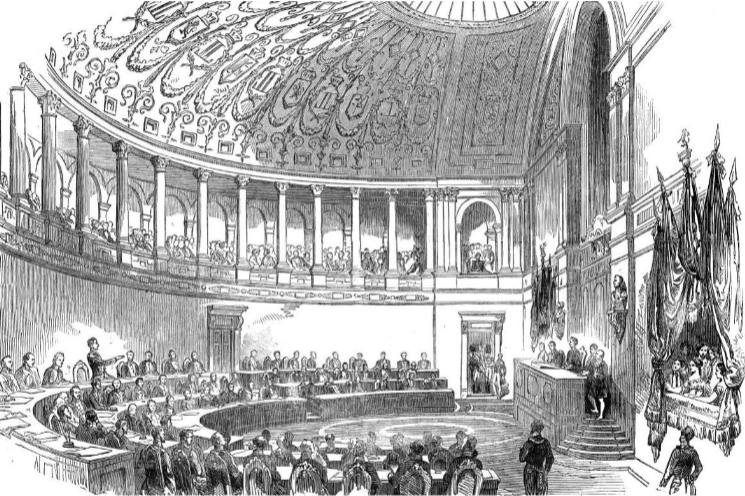

In November 1849, the Senators met for the first time in their new 'debating chamber'. The room was not fully completed: the coats of arms of Belgium had been carved into the woodwork behind the President’s rostrum and the busts of Leopold I and Louise-Marie had been placed in niches to the left and right, but the dome (decorated with the monogram of Leopold I and Louise-Marie and the shields of the provinces) had not yet been decked out in all its colours. Huge canvases had been stretched around the perimeter of the hemicycle to conceal the lack of panelling.

At the front, on the wall behind the presidential platform, places had been set aside for three paintings.

In September 1853, a large allegoric canvas entitled 'La Belgique fondant la monarchie'[ 1 ] (Belgium establishing the monarchy) or sometimes 'Les Provinces Belges' (The Belgian Provinces) was added to the central position. Not a lot is known about it. It was a large allegorical painting representing 'Belgium surrounded by personifications of the provinces or major cities in the country, each bearing the symbol of the industry or trade they represent'.[ 2 ]

Although they had commissioned this painting in 1848 from Edouard de Biefve (1808-1882), the Senators were apparently a little disappointed... One critic said of it: 'Never has a painting been more glacially official!'[ 3 ] When, a few years later, the painter offered to provide paintings for the other two places that were still empty and the Minister for the Interior approached them again, the Senators politely declined his offer suggesting that 'Mr Biefve has been less successful with this work than in most of his other productions'. And since the cost was to be covered by the Senate budget, it was for the Senate to now decide on the artist that would decorate its plenary room.[ 4 ]

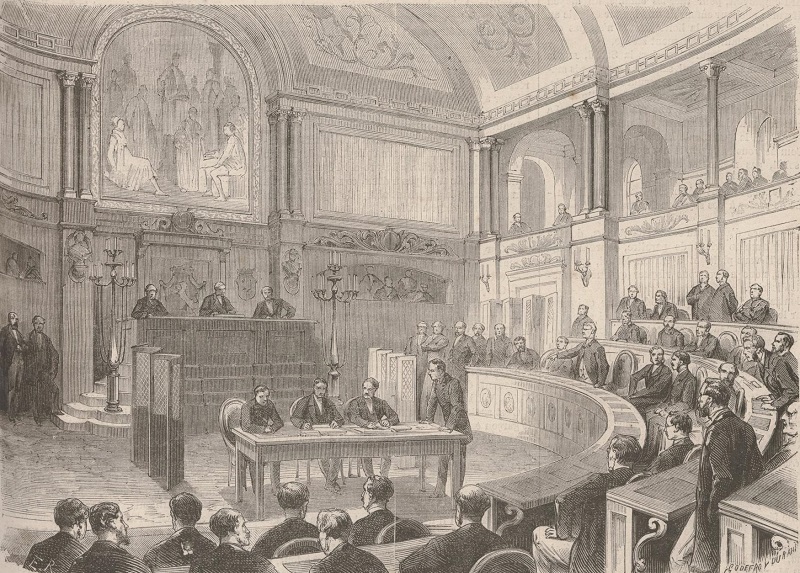

In the meantime, Louis Gallait had produced the hemicycle's historical 'portraits' gallery. These portraits were put in place around 1878-1897 in the spaces that foreseen in the mahogany woodwork, which had been completed in the summer of 1864.

Absolutely delighted and enthusiastic when these portraits of historical figures were unveiled (even if it had taken the painter almost 16 years to finish them and had sorely tried their patience!), the Senators asked Gallait to also provide portraits of Leopold I and Louise-Marie and of Leopold II and Marie-Henriette. The idea was that they should occupy the two spaces that were still empty, above the press galleries and on either side of the presidential platform and the painting by Edouard de Biefve.

The sketches were met with enthusiasm when they were presented in 1882. But Louis Gallait died in November 1887, still busy on the project: the portraits of Leopold I and Louise-Marie had been completed, but that of Marie-Henriette had barely commenced, while the portrait of Leopold II had not even been started. It would seem that the artist had also done sketches for the central part in which he would have put an allegory of the swearing in of Leopold I.

The paintings of Leopold I and Louise-Marie adorned the large wall of the Senate debating chamber from 1887 to 1896, but we have not been able to trace any images of them to date.[ 5 ] This may not be by chance: the contrast, and indeed the total lack of harmony, with the de Biefve painting would have been painful on the eyes!

To the Jacques de Lalaing 'fresco'

The fact remains that on 18 March 1890, Count Charles de Mérode Westerloo, President of the Senate, wrote to Count Jacques de Lalaing, an artist and painter, to entrust to him 'the task of finishing decoration of the sessions room, left unfinished by the death of Mr Gallait', arguing that the 'Senate had found no-one was better suited than yourself to continue the work of this eminent artist'.[ 6 ]

Jacques de Lalaing (1858-1917), this 'gentleman artist',[ 7 ] was indeed highly acceptable to the Senate.

A painter, he was trained in the studio of Jean-François Portaels from 1875, but also kept company with the painter Alfred Cluysenaar, and more importantly Louis Gallait. Attracted by line, form and volume rather than colour, he also learnt to sculpt from Thomas Vinçotte in 1884.

His first paintings were historical subjects, but he also produced portraits, often of the high society he frequented (as a painter and as one of its members), including Senators and their wives. These included Mrs de Favereau in 1897, whose husband, a future President of the Senate, held a seat in the House of Representatives. In 1899, he also painted a portrait of Nathalie de Mérode Westerloo, the wife of Count Henri de Mérode Westerloo. When the Count, like his father Charles, became President of the Senate, he asked de Lalaing to produce his official portrait of office (finished in 1905). That of Senator Georges Dupret in 1907 should also be mentioned.[ 8 ]

Throughout his long career, he was approached with numerous official requests and orders. Some appreciated his work since 'Far from being an anti-establishment artist, he adopted classical and formal forms alluding to a degree of aesthetic durability, placing his work in a continuum that would stir memories and strengthen historical identity'.[ 9 ] Which was exactly what the Senators were seeking for their plenary room...

In addition, Jacques de Lalaing had a personal fortune and was not, therefore, unlike some of his contemporaries, an artist 'in need' or obliged to live from his art. The Senate archives show that before an order was placed for large canvases for the hemicycle, he was asked to give his ‘price’. De Lalaing replied: 'Your question of this morning left me as embarrassed as I was when the Mayor of Brussels asked me to estimate the work I have to do on the Town Hall. My reply to you, as it was to him, is that I have nothing on which to base any assessment; any figure I gave would therefore be arbitrary; I feel, in this regard, as though I am being asked to count my chickens before the eggs have even been laid. I will therefore defer to the discretion of the Quaestors or any expert that these persons may wish to appoint and undertake to abide by the resulting decision'.[ 10 ] A letter from the City of Brussels informs the Senators that the Count will be paid '700 francs per square metre' for the canvases for the Town Hall! The Senate adopted the same system of payment... which was more akin to that used in construction than for artists and painters... But it probably helped with the Senate’s finances!

Acknowledging Jacques de Lalaing to be a man of great culture, the Senators left to him the initial choice of historical programme for the canvases. As a sculptor, he immediately perceived the fluid and dynamic whole that he could propose: 'in a series of distinct groups, although linked to each other by their key attributes, I would like to unfold, on the surface of the three panels, the different phases of the history of our country, subdivided not by reigns but by era and influences. In a word, to represent the political waves that have successively passed through Belgium'.

But as a painter, he wanted this series to be 'picturesque', 'episodes typical of the time, with a pictorial aspect'. Taking the opposing view to de Biefve, he declared: 'only Literature can impart the Philosophy of History. Painters above all must seek the picturesque. History painting, wishing to express occasions undoubtedly solemn and important, but portrayed from a purely moral viewpoint, offering nothing for the eyes other than a treaty being signed or a ceremonial royal entry, has often been boring.'

He therefore chose to paint tragic moments from the history of our regions: 'I feel a need to apologise for having placed the spotlight on the sorrowful episodes of our history and want to explain my reason for this choice: Firstly, prosperity offers no pictorial interest; secondly, painting can only reflect a crisis and not a state of being, and finally, I deduce from that well-known phrase ‘Happy are the people whose history is boring’ that the joyous phases of the Belgian people would be as boring to paint as to write.'[ 11 ]

De Lalaing proposed to produce drawings in pastel of everything that he imagined, deeming this medium to be preferable to written text or a sketch. On 20 November 1890, the President of the Senate and the Quaestors came to see him in his studio, located within walking distance of the Parliament at 29 Rue de l’Activité (since renamed Rue Jacques de Lalaing; the studio still exists and now houses a 'Food & Art Gallery').

Senator-Quaestor Edmond Willems, the heir to the Artois breweries in Louvain (and who seems to have been the Viscount Vilain XIIII behind the initiative of choosing Jacques Lalaing for the canvases), made three remarks to him: there are too many horses in the left part devoted to 'municipal militias' at the battles of the Golden Spurs and Rozebeke; in the central part, the Louis XIV wars and the Spanish era should be reversed so that they are chronological in order, and finally, 'the harsh historical truth' of the programme should be toned down. De Lalaing agreed to certain changes, except the last remark - he had the opportunity to consult the Prime Minister of the time, the Catholic Auguste Beernaert whose sister was a painter, who did not share the 'concerns raised by the programme' among the Quaestors. Willems gave in and the Senate Bureau accepted the programme as sketched by the artist in December 1890.

At the end of January 1893, following a concerned letter from the Senate, Jacques de Lalaing confirmed that he had finished his preparatory sketch of the three panels and promised to finish the first panel by the start of 1894.[ 12 ] At the end of September 1894, the left panel was indeed finished and the two others had been sketched. While Jacques de Lalaing went to Paris to look for costumes for the second panel, the Quaestors visited his studio. This is what they found.

On the left panel, the 'citizen militia and trades people surrounding the guild banners and waging a glorious battle, at formidable odds, against the French cavalry', 'this unevenly matched war, of which the Battle of Courtrai was the climax and the defeat of Rozebeke the disastrous epilogue'. Then above this 'the power of the house of Bourgogne, the moment when Duke Charles the Bold dragged his prisoner, Louis XI, to witness the sight of the town of Liege, which the King of France had encouraged to revolt, going up in flames'.

Photo © KIK-IRPA, Brussels

On the central panel, devoted to the Spanish and French period, 'I wanted to cast the shadow of the Duke of Alba over the scene behind showing the Count of Egmont and the Prince of Orange at Willebroeck, when they exchange the prophetic words, "Adieu lackland Prince; Adieu Count without a head", a moment which bears witness to the solidarity in the aspirations of the Flemish and the Dutch'.

'Then in the forefront, the decorative but, for us, disastrous era of the wars of Louis XIV in Belgium, showing the battle involving the Marlborough and Prince Eugene coalition against the invader (on the plains at Ramillies and Malplaquet) and in the background, the bombardment of Brussels by Marechal de Villeroi'. 'Above this group, in the arch, two symbolic figures - History and Destiny.'

Finally, to the right, 'the end of Austrian domination of Belgium, the Brabant Revolution, rising up in the persons of de Vonck and Van der Noot, against the Government of Joseph II. This being followed by the entry into Belgium by Dumouriez, implanting in our country the flag and ideas of the French Revolution, and finally the moment when the First Empire collapsed on the plains of Waterloo thanks to the efforts of the allies, with Napoleon turning around to call in vain to Marshall Grouchy for help'.[ 13 ]

This dense and compact programme was not easy to grasp. One needed to be very familiar with our regions to take in all the details. At the inauguration of the panels in 1896 and the visit by the press, de Lalaing was asked to draw up a 'short notice' that would be printed in 2,000 copies.[ 14 ]

Nor do the colours chosen by the artist for his canvases make them easier to understand. They are, however, very typical. With de Lalaing, 'the colours are often dull, being secondary to the form and volume.'[ 15 ] The Quaestors knew this. The post-scriptum that Viscount Vilain XIIII added to his note to the Greffier of the Senate before their first visit to the studio to see the first of the panels speaks for itself: 'I fear he has just given us the same shades of grey as for the Town Hall.'[ 16 ] De Lalaing anticipated their reaction in his invitation: 'I hope these Gentlemen will not be alarmed by the rather severe tones of this panel. These are required by the subject matter. I am reserving all the brilliance that the Louis XIV era demands for the central panel.'[ 17 ]

It was a well-dampened brightness, Jacques de Lalaing remaining faithful to himself in this regard. Yet, the light from the skylight at the top of the Senate dome, which was originally closer to the canvases, would have brought out the colours, and in particular, those of the clothing, which had required a lot of research, and of the horse blankets, the range of which is much more subtle and nuanced that it appears at first sight. One can also see de Lalaing's plays of contrasts using whites and reds, for example those that link trigonally the figures of Napoleon, Dumouriez and Joseph II in the canvas to the right. This is in contrast to the left panel where, as the journalist from the Journal de Bruxelles attending the inauguration remarked, notably with regard to the municipal militia: 'Colour means nothing to him, neither as a source of joy, nor as a means of expression. His left panel is, from this point of view, almost stupendous. Everything is brown, grey, black and cold. The standards are grey, without any hint of colour.'[ 18 ]

Jacques de Lalaing also made use of the light in the sky to 'illuminate' the backgrounds to his canvases and achieve contrasts. The figures of Charles the Bold and Louis XI therefore emerge from the blaze of the fire of Liege; those of Marlborough and Eugene of Savoy face the light generated by the bombardment of Brussels. On the third canvas, 'in the background to the picture the three allies, and Blücher, who is joining them, are at full gallop, silhouetted against the salmon sky of all good battles'.[ 19 ]

The press was invited on 11 February in the afternoon. The articles were enthusiastic positive overall, even if some agreed that the symbolic figures of History and Destiny, as well as the floating figure of the Duke of Alba in the middle panel, were less successful. But all admired the art of the summary and composition that de Lalaing showed (somewhat reminiscent of Bernard van Orley, another Brussels artist[ 20 ]), and his great mastery in depicting the movements of horses, which was his signature trait.

King Leopold II, after announcing his visit on 11 and 19 February, finally came to see the canvases on 20 February 1896 in the afternoon. He was accompanied by Princess Clementine.[ 21 ] Received by the Minister for Fine Arts, Viscount Vilain XIIII, Baron Snoy and the President of the Senate, t’Kint de Roodenbeke, the latter explained to them the symbolism of the paintings. They admired them for 30 minutes.

- Belgian Senate archive, de Biefve file: on 13 August 1848, when the debating chamber was under construction, the Senate had asked the Minister for the Interior to agree to a painting by de Biefve 'an artist who was able to combine highly skilful execution with an eminently national choice of subject matters'. All trace was lost of this painting by Edouard de Biefve, a painter of history very much in favour at the time, after it was taken down in 1896 to be replaced by the 'historical fresco' by Jacques de Lalaing. Preparatory drawings are held at the Royal Library (KBR), Prints Room. See Judith Ogonovsky, 'Edouard de Biefve (1808-1882), une étoile filante au sein de l’art officiel belge', in Revue belge d'archéologie et d'histoire de l'art, no. 71, 2002, p. 59-88. [ back ]

- Belgian Senate archives, de Biefve file, letter from Charles Rogier, Minister for the Interior, responding to the Senate Quaestors, 25 March 1852. [ back ]

- Lucien Solvay, 'Notice sur Edouard de Biefve, correspondant de l’Académie', in the Annuaire de l’Académie royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, 1915-1919, p. 68. [ back ]

- Senate archives, de Biefve file, letter from the Senate President, the Prince de Ligne, to the Minister for the Interior, 14 November 1876: "Monsieur de Biefve a été moins heureux dans cette œuvre que dans la plupart de ses autres productions." [ back ]

- The portraits were supposedly then hung at the Minister of Finance office (at 11 Rue de la Loi?). [ back ]

- Belgian Senate, de Biefve file, letter from the Senate President, the Count of Mérode Westerloo, to Jacques de Lalaing, 18 March 1890. [ back ]

- Charles Lagasse de Locht in Bulletin des Commissions royales d’Art et d’Archéologie, speech given at the session on 13 October 1917, on the death of the artist. Cited by Catherine Leclercq, Jacques de Lalaing, artiste et homme du monde (1558-1917), Classe des Beaux-Arts (Fine Arts Class), Belgian Royal Academy, Brussels, 2006, p. 37. [ back ]

- The portrait of Henri de Merode Westerloo can be found in the Senate; that of Georges Dupret is still with his family. Our thanks to Thierry Scaillet for drawing attention to this last portrait. See on this subject: Thierry Scaillet and Dorothée Schneider, Histoire de la famille Dupret, 17e-20e siècles. En affaires et en politique, de Ath à Bruxelles, Brussels, 2019. [ back ]

- C. Leclercq, Jacques de Lalaing, artiste et homme du monde (1558-1917), Classe des Beaux-Arts, Belgian Royal Academy, Brussels, 2006, p. 49: "Loin d'être un artiste contestataire, il adopte les formes classiques et solennelles qui font référence à une certaine pérennité esthétique qui inscrivent l'œuvre dans une continuité apte à revivifier la mémoire et à renforcer une identité historique." [ back ]

- Senate archives, de Lalaing file, letter from Jacques de Lalaing to Baron Oscar Pycke de Petteghem, 18 February 1890: "Votre question de ce matin m'a remis dans le même embarras que jadis quand le Bourgmestre de Bruxelles m'a demandé d'estimer le travail que je dois exécuter à l'Hôtel de Ville. Je vous répondrai, comme à lui, que je n'ai aucune base d'appréciation, le chiffre que j'indiquerai serait donc arbitraire, que je me sens à ce sujet dans la situation de celui qui vend la peau d'un ours qui court encore. Je m'en rapporte donc à l'appréciation de la Questure ou de l'expert que ces messieurs voudront bien désigner, en m'engageant à accepter la décision qui en résultera." [ back ]

- Senate archives, de Lalaing file, undated letter, but probably the summer of 1890, from Jacques de Lalaing to a 'Dear Sir', probably E. Willems. [ back ]

- The delay in completion is explained by the research that Jacques de Lalaing had to undertake, but also due to concurrent works: frescos for the Brussels Town Hall, Coquilhat monument, portraits, etc. In addition, proposals to expand the plenary room had been raised and examined in 1884-85 in order to take into account the increase in the number of Senators. These could have had an impact on the size of the de Lalaing canvases. He warned the Quaestors about this, but ultimately the works were postponed until 1902-1904. At that time, the canvases mounted with white lead were detached and replaced, the canvas in the middle more set back from the two others, as the artist had initially planned. [ back ]

- 1890 programme and 1896 explanatory notice by de Lalaing. [ back ]

- The canvases were mounted in white lead on the walls of the Senate by Charles Léon Cardon (offer of 27 December 1895). General Archives of the Kingdom, Ministry of Public Works, Civic Buildings, file 70. [ back ]

- C. Leclercq, op. cit., p. 22. [ back ]

- Senate archives, de Lalaing file, letter from Vilain XIIII to the Greffier (Warnant) of 4 December 1894. [ back ]

- Senate archives, de Lalaing file, letter from J de Lalaing to Viscount Vilain XIIII, towards the end of September 1894. [ back ]

- Senate archives, de Lalaing file, letter from Mr de Lalaing, 'The paintings of Mr de Lalaing to the Senate', in Le Journal de Bruxelles, Brussels, 23 February 1896. [ back ]

- Senate archives, de Lalaing file, 'The Senate paintings', in La Réforme, 12 February 1896. [ back ]

- The personal journals of Jacques de Lalaing have been conserved in part. He happily uses words from the Brussels dialect ('Brusseleer') such as 'drache' (downpour), 'stoefer' (braggart), 'duive kot' (dovecot ), 'moi, j’ai le flauw' (I’m feeling a bit limp), and 'zwanze' (drivel). Catherine Leclercq highlights these words in her monograph. [ back ]

- Le Journal de Bruxelles, 20 February 1896, p. 1. L'Indépendance belge, 21 February 1896, p. 1. [ back ]

© Belgian Senate